Carrie Harris, a stewardess aboard the Portland, died when the steamer went down in November 1898. Her sister Ellen Johnston filed a claim for Carrie's wages.

Reconstructing the List of the Steamer's Crew

On November 27, 1898, the steamer Portland departed Boston for her scheduled run to Portland, Maine. She was never seen again. That evening a storm arose in the waters off New England. Before it abated the following day, hundreds of vessels and shore properties were damaged. The Portland was lost with no survivors, and that storm has come to be known as "The Portland Gale." To this day it is not known exactly how many passengers were aboard or who they all were. The only passenger list was aboard the vessel. As a result of this tragedy, ships would thereafter leave a passenger manifest ashore. It is estimated that 190 died that evening, passengers and crew. But if the passengers cannot all be positively identified, what of the crew?

This article is an attempt to discover information about the men and women who made up the crew of the Portland using records in the National Archives and Records Administration–Northeast Region (Boston). The first place to look would be the customs records of Portland, Maine, the steamer's home port. Unfortunately, many 19th-century records are incomplete, and there are few records in the Archives for this port. For the Portland, there are no crew lists, shipping articles, manifests, or vessel documentation.

There are records related to the Portland in the Life Saving Service station logs along the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. These provide information on the aftermath of the storm, noting the bodies and artifacts washed ashore. At the Cahoons Hollow station, on November 28, 1898, the body of George Graham, a Negro, washed ashore. He is identified by name in the log entry, and he is the only crew member whose body was identified at the time of recovery.

The case files of the U.S. District Court at Portland, Maine, contain the petition for limitation of liability filed by the Portland Steamship Company in response to the civil suits filed by the estates of deceased passengers. There is little information about the crew. Eventually the court ruled the sinking an act of God, thus absolving the company of all responsibility. The suits were withdrawn.

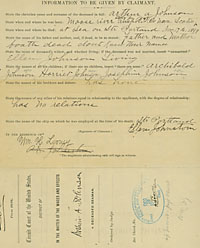

In the records of the U.S. Circuit Court, Maine, one finds the case files of deceased and deserted seamen, 1873–1911. Under an act of June 7, 1871, Congress authorized the office of "shipping commissioner" in federal circuit courts whose jurisdictions included seaports or customs ports of entry. Among their duties, commissioners collected the wages due to deceased seamen from the vessel's master or owners and turned the money over to the court for delivery to the legal heirs. Unclaimed monies would eventually be turned in to the U.S. Treasury. Claimed funds would be paid only after the court was satisfied that the proper person was getting the money. To that end, these case files provide extensive family information through preprinted forms or affidavits or both.

|

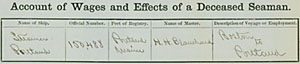

The wage papers filed with the circuit court can be a valuable source of genealogical information about lost seamen. This account documents wages owed to Arthur Johnson. |

The first is that of John C. Whitten, a watchman survived by a wife and four children. He was owed $35.00 for one month's wages. His widow, Lettie A., filed the claim on behalf of herself and her children, ages 6 to 12.

The 1900 U.S. population census shows Lettie, age 32, residing at the "Invalids Home" in Portland, Maine. I called the Maine Historical Society in Portland to learn what type of institution this was, and I was informed that this was a home "where self-supporting women could be cared for at a nominal price when by reason of overwork or illness they required the rest and nursing which could not be secured elsewhere." Of the four children, daughter Lettie, age 8, was placed as a "ward" with a private family; two of her brothers were at the Good Hill Farm, Fairfield, Maine; and the third son could not be located in the census. Further research into the Home records and Cumberland County Court records might reveal details on these events. One cannot but wonder if the dispersal of the family came about as a result of the husband's death in 1898.

Where crew lists exist, it is an easy matter to identify race and origin. In cases such as the Portland,census records can reveal that information. African Americans served as crew on many of the coastal steamers in the 19th century. From the 1900 U.S. census and the 1901 provincial censuses of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, I learned that several members of the crew, besides George Graham, were black, and that many had been born in Canada.

For Ellen Johnston of Portland, Maine, the sinking of the vessel was doubly tragic. Both her husband, Arthur, and her sister, Mrs. Carrie E.M. Harris, were lost. Ellen filed a claim for her husband's wages on December 19, 1898. She stated that her husband had been born at Moose River, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, on April 2, 1848. His parents were both deceased, and his survivors included three children, Archibald, Harriet, and Josephine. The 1900 census of Portland, Maine, showed Helen [sic] with her children and revealed that they were black, all born in Nova Scotia.

On that same day, Ellen also filed a claim for the wages of her sister. From this we learn that Carrie was born at St. Marys Bay, Nova Scotia, November 10, 1840, to David and Cellia [sic] Sibley, both deceased. She was a widow and had no children. Her siblings included one brother, John Sibley, and two sisters, Cellia Sibley, and Ellen Johnson [sic]. In January of 1899, both John and Cellia Sibley sent affidavits from Nova Scotia to the court in Portland, asking that their share of Carrie's wages be paid to their sister, Ellen Johnston.

Carrie Harris's sister Cellia Sibley sent the circuit court her consent for Ellen Johnston to receive the balance of Carrie's wages.

When the Portland went down on November 27, 1898, the records on board went down with her. But by using other sources, particularly the 1900 U.S. federal census and the 1901 Canadian census as well as the records of deceased and deserted seamen of the U.S. Circuit Court in Maine, researchers can reconstruct information about the crew. The records give not only the names of the crew but can flesh out their lives as well.

Click here for the Final Crew List of the Steamer Portland.